A Literary Review of Armando Heredia’s “Chasing the Sun”

Armando Heredia’s triptych, Chasing the Sun, is a profound and cohesive exploration of the American mythos of escape and the complex, often painful, reconciliation with one’s roots. Presented as three distinct yet interconnected poems—“Dream Sequence,” “Chasing the Sun,” and “Head’n West”—the collection functions as a nuanced narrative arc, moving from inherited longing, through the act of departure, and culminating in a weary but purposeful return. It is a masterful study of how legacy, memory, and landscape shape identity.

I. “Dream Sequence”: The Haunting of Legacy

The collection opens not in the physical world, but “back in the ether,” establishing memory and familial influence as the primordial forces driving the narrative. Heredia deftly uses fragmented, almost ghostly imagery to build a foundation of inherited restlessness. The figures of the father, the brother (“almost a stranger”), and the uncle are not fully realized characters but mythic archetypes, “spoken only in whispered tones.” This deliberate vagueness universalizes them; they become every family’s stories of adventure and danger that tantalize the next generation.

The poem’s power lies in its refrain: “That makes me want to ride.” The verb “ride” is crucially ambiguous—evoking both the motorcycle of the uncle’s “v-twin” and the train that becomes a central symbol in the following poem. It is a primal urge, passed down like a genetic trait, suggesting that the desire to escape is itself a form of inheritance. The repetition of “danger” and “whispers” creates a hypnotic, compulsive rhythm, mirroring the inescapable pull of a destiny one did not choose.

II. “Chasing the Sun”: The Bittersweet Act of Escape

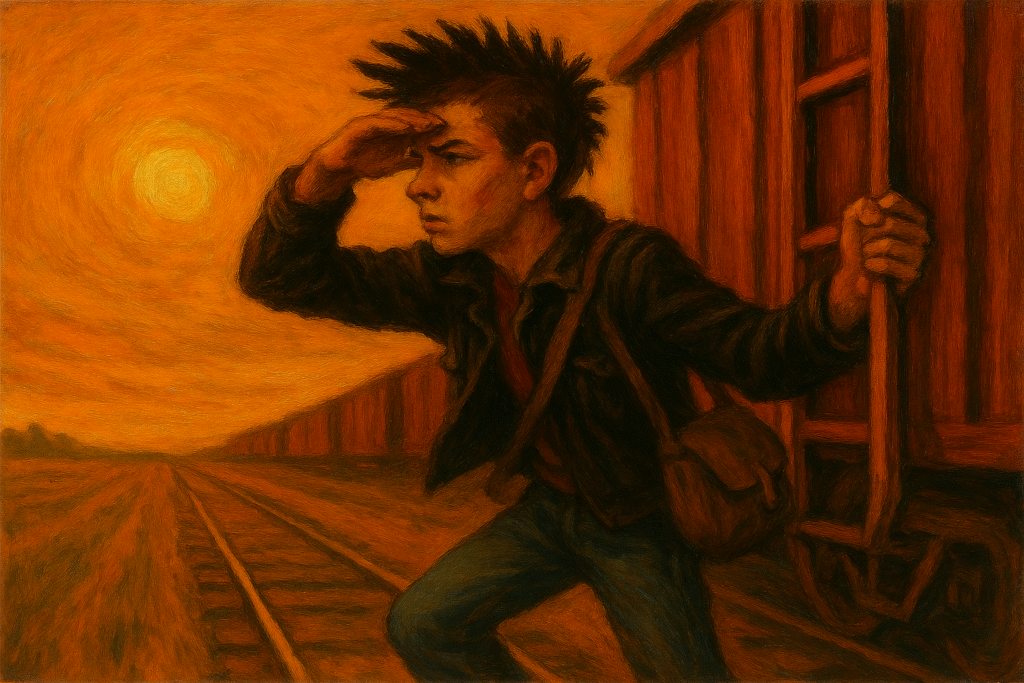

Where “Dream Sequence” is all haunting potential, the titular second poem crashes into the reality of action. Heredia captures the quintessential youthful idealism of small-town life with the potent image of “Boys playing at the tracks,” who “swore we’d board the train / Someday, and Never look back.” The capitalizations on “Someday” and “Never” elevate these concepts from mere words to sacred vows, highlighting the absolute faith of youth in a future elsewhere.

The poem’s central tension is revealed not in the escape itself, but in its aftermath. The poignant receipt of a letter reveals a friend who has “finally caught that train,” yet the victory is undercut by a profound melancholy. Heredia subverts the classic escape narrative with the brilliant line: “But you’re still facing west / Cause maybe this is better / But you’re still looking for best.” This exposes the perpetual motion of desire—the sun, the symbol of a better life, is always on the horizon, forever receding. The pleading refrain, “Oh, someone stop the sun,” is a cry of existential exhaustion, a realization that the chase is endless and daylight—time, opportunity, youth—is always running out.

III. “Head’n West”: The Circular Journey Home

The final poem represents a stunning and mature resolution to the collection’s central conflict. The direction remains “west,” but the motivation has fundamentally shifted. No longer is it a frantic “chase”; it is now “Driving into the sunset,” which is explicitly equated with “head’n home.” The journey has come full circle, both geographically and emotionally.

Heredia introduces a layer of profound literary depth through introspection and regret—elements absent from the naive fantasies of the previous poems. The confession, “I won’t lie and say I wouldn’t change a thing,” is a moment of stunning vulnerability. He rejects facile clichés of regret-free living, instead acknowledging that “those regrets / Made this journey harder than it need be / And the who they made me / Isn’t the me I planned to be.” This is the core of the collection’s wisdom: identity is not a pristine plan achieved but a mosaic built from choices, mistakes, and detours.

The imagery softens from the sharp, dramatic symbols of trains and tracks to the gentle, natural fading of light: “the stars are flickerin’,” “an Orange horizon line / Under an indigo blue sky.” The mood is no longer one of frantic pursuit but of quiet acceptance and weary resolution. The journey ends not at a dramatic destination, but simply “where it ends,” in the peace of returning “back to you, back where I belong.”

Conclusion: A Unified American Lyric

As a triptych, Chasing the Sun succeeds as a unified and powerful literary work. Heredia weaves a consistent symbolic tapestry—trains, wheels, horizons, and familial ghosts—to explore the cyclical nature of seeking. The collection argues that the true journey is not about merely arriving at a new place, but about understanding the forces that propelled you forward and ultimately integrating that understanding into a sense of self and home.

It is a deeply American narrative, echoing the spirit of Whitman and Kerouac, but filtered through a modern, introspective lens that values emotional truth over romanticized adventure. Heredia’s work is a poignant reminder that we often must chase the sun to the highway’s end only to discover that home was both the point of origin and the final destination all along.