Release Date: February 14, 2026

Life in the barrio is often a shuffle between “gray death and explosions of life.” It is a place where survival is a daily grind, and hope often comes in the form of a two-dollar slip of paper.

On February 14, 2026, I am proud to release my latest project, “The Lottery.” This isn’t just a song, and it isn’t just a story. It is the next evolution of the MusicScape Storyline.

What is a MusicScape Storyline?

For those following my work, you know I am always looking for ways to bridge the gap between narrative and music. A MusicScape Storyline is a “lyric audiobook”—an immersive audio format that weaves spoken word, character dialogue, and lyrical musicality into a single, cohesive experience.

Unlike a traditional song, it follows a linear script with characters and a plot. Unlike a standard audiobook, the story is driven by rhythm, melody, and the emotional texture of a musical composition. It is theater for your ears, designed to drop you directly into the scene.

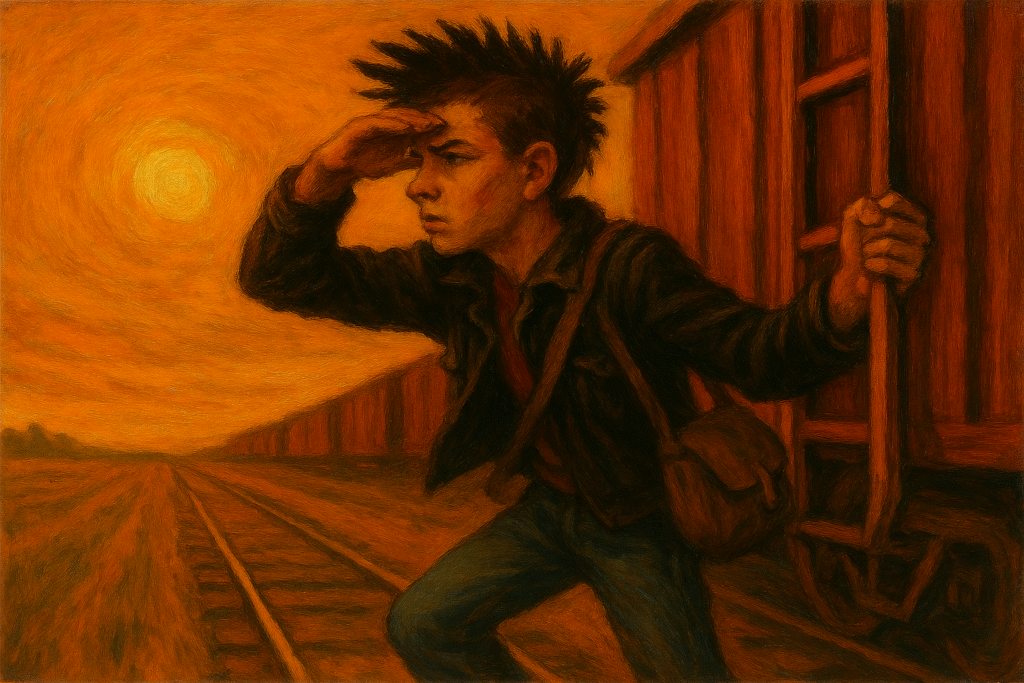

The Story of Bento

“The Lottery” introduces us to Bento, a young man trying to keep his head down and his eyes on the pavement. He lives in a world defined by “needs and bad decisions,” raised by his grandmother after his mother was incarcerated.

Bento has a ritual. Every week, since his eighteenth birthday, he buys a lottery ticket. He plays the same numbers every time—the date his mother was taken away. To him, they are “lucky numbers, stupid numbers.” They are his only ticket out of a neighborhood where the sidewalks are grimy and the options are few.

But the neighborhood has other plans.

Caught between the pressure of the local gang, Los Morenos, and the weight of his family’s history, Bento finds himself backed into a corner.

What starts as a typical day of dodging trouble spirals into a

life-altering ultimatum: join the “family” business or face the consequences.

The Gamble

“The Lottery” takes you through 24 breathless hours in Bento’s life. From the fluorescent hum of the 7-Eleven where he buys his ticket, to the terrifying silence of a bank lobby where he never intended to be.

The story asks a simple, terrifying question: What happens when your “lucky day” finally arrives at the exact moment your luck runs out?

It is a story about the irony of fate, the trap of circumstance, and the desperate desire to find a place with “pastel colors and clean sidewalks.”

Listen on Valentine’s Day

This story is gritty, emotional, and intense. I can’t wait for you to hear how Bento’s story unfolds—but I won’t spoil the ending here. You’ll have to listen to find out if Bento finally gets out.

“The Lottery” drops on February 14, 2026.

Available for streaming on:

- Apple Music

- Spotify

- Amazon Music